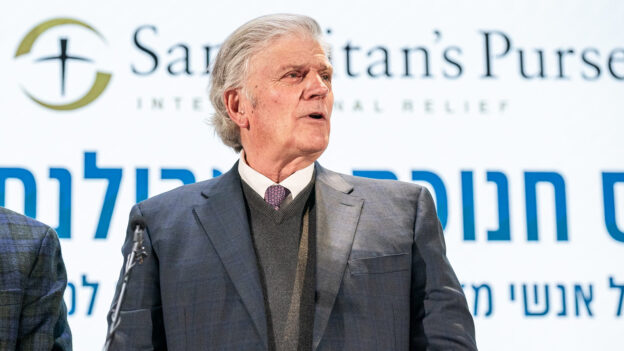

By any measure, Franklin Graham stands at the summit of evangelical influence. As president of both Samaritan’s Purse and the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA), he commands vast resources and global reach. Yet this summer, Graham quietly pulled both ministries out of one of evangelicalism’s most respected watchdog groups the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA) after the organization introduced new standards meant to safeguard not just finances, but integrity itself.

Graham’s reason? A conviction that the ECFA, in his words, was becoming “the moral police of the evangelical world.”

For decades, ECFA accreditation has been a badge of legitimacy among Christian nonprofits. To earn it, organizations must open their books, maintain independent boards, and follow the group’s “Seven Standards of Responsible Stewardship.” The premise is simple: transparency breeds trust.

But in recent years, financial honesty has proven insufficient. A wave of high-profile scandals from megachurch pastors confessing undisclosed “sins” to sexual abuse revelations and cover-ups has shaken the evangelical establishment. The ECFA’s new “leader care” standard is its attempt to address that moral rot at the roots.

Under the new policy, every member organization must create a formal care plan for its senior leader. The plan is meant to include regular spiritual check-ins with a board-appointed team, along with time set aside for rest, retreats, and even medical evaluations. The idea is both pastoral and practical: prevent burnout before it curdles into abuse or corruption.

To many Christian leaders, this move felt overdue. The heads of the National Association of Evangelicals and the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities endorsed the measure, joining hundreds of churches and ministries who saw it as a needed correction a safeguard for souls as well as balance sheets.

But Franklin Graham didn’t see it that way.

In a letter to ECFA’s president, Graham argued that while the council had proven expertise in financial management, it had no business supervising spiritual formation. The new rule, he wrote, “deals with personal spiritual maturity and behavior matters clearly outside the scope of ECFA’s expertise.”

In his view, this wasn’t accountability it was overreach.

For Graham, who has long projected an image of rugged evangelical autonomy, the notion of an external body evaluating a leader’s “spiritual health” seemed both invasive and misplaced. It’s hard not to sense a deeper discomfort here not just with bureaucracy, but with the idea that moral oversight could be institutionalized at all.

The decision carries a poignant symmetry. Franklin’s father, Billy Graham, helped found the ECFA back in 1979, along with World Vision’s U.S. branch, in an effort to restore public trust after a string of televangelist scandals. That the younger Graham would now exit the same organization signals a generational turn away from the shared accountability his father once championed, and toward something more individual, more defensive, perhaps more corporate.

Also Read: 55 Amazing Bible Verse Tattoos for Men: Wear Your Faith with Boldness

Samaritan’s Purse and the BGEA are, financially speaking, powerhouses. The Boone, North Carolina–based Samaritan’s Purse reported $1.4 billion in net assets last year, while BGEA, which changed its tax status in 2016 to classify as an “association of churches,” now operates without the public transparency of a typical nonprofit. According to MinistryWatch, it brings in over $224 million annually.

Critics and allies alike have weighed in. Mark DeMoss, a longtime evangelical public relations figure and former advisor to Graham, wrote an analysis concluding that the new ECFA standard however well-intentioned would likely fail to prevent the very abuses it seeks to curb. “No standard, particularly one as decidedly vague as this one,” he argued, “can prevent bad behavior.”

It’s a fair point: you can’t audit a soul. Yet others insist that the absence of structured care has allowed too many leaders to drift into isolation and moral failure. Theologian Scot McKnight, who has written extensively about Christian leadership, said the problem isn’t the principle but the implementation. A care team, he suggested, should consist of trained spiritual directors, not board members who might be beholden or starstruck by the senior leader they’re meant to guide.

As of 2025, ECFA’s retention rate remains strong 97% and more than 140 nonprofits have applied for membership this year. The leader care standards will become mandatory by 2027, signaling that most ministries are willing to embrace this new layer of moral scrutiny.

Still, Graham’s departure lands with a thud in the broader conversation about authority, transparency, and trust within American Christianity. It raises the uncomfortable question of who, if anyone, has the right to hold spiritual power accountable.

Graham seems to believe such oversight belongs to God alone not to boards, auditors, or committees. But for an evangelical movement still reckoning with its own abuses, the timing and symbolism of his exit may feel less like an act of conscience and more like retreat.

In the end, the tension is perennial: faith wants freedom, but freedom without accountability too easily drifts toward ruin. The ECFA is trying to thread that needle to remind the church that integrity isn’t only about money, but about the soul that spends it.